What do you think?

Rate this book

716 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1992

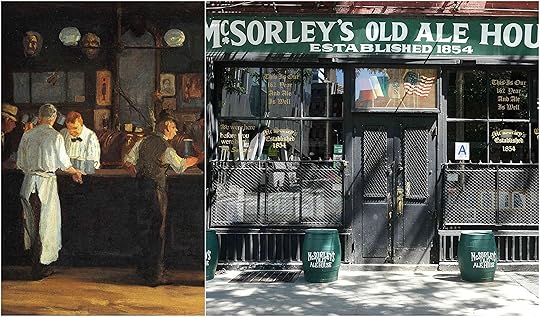

At that time, in 1894, the Bowery was just beginning to go to seed; it was declining as a theatrical street, but its saloons, dance halls, dime museums, gambling rooms, and brothels were still thriving. In that year, in fact, according to a police census, there were eighty-nine drinking establishments on the street, and it is only a mile long." p. 128

He was a little like one of those men who are too shy to talk to strangers but not too shy to hold up a bank. (1964)There's no place quite like the United States when it comes to self-mythologizing. And within that scope, it's a simple hop skip and a jump to the Big Apple, the ever present example used to clarify the word 'metonymy', that incessant redundancy that has gone on for so often and so long: New York, once New Amsterdam, New York. Population wise, one out of every 39 US citizens is a New Yorker, so if it seems like folks in the books and the movies and the social medias never shut up about the place, even the pure numbers game makes it hard to avoid picking up some low level familiarity with the sociocultural juggernaut. With me, not even the dying days of the Phantom of the Opera musical succeeded in spiriting me away to that place, and while I've certainly read my fair share of NYC grounded lit in various 1001-minded lists, this is the first read in a while where I was so actively aware of the city and its mythos. Much of it is as repetitively obnoxious as is any US city that thinks itself immune from being another Omelas, and the saving grace of a writer like Mitchell is the ability to spin a tale of art and economics and make the details human without giving into either pity or self-adulation. True, there's some self-serving horseshit, especially in the writings involving g*psies, which is what knocked off that last half star. However, the trick to NYC is how little it takes to draw a reader in, whether it's the past or the present, the fresh or the polluted, the enfranchised and the otherwise: all you need to do is pay less attention to the selling and more to the recording, and the audience will follow.

I was below eating lunch and Morris was on deck sorting a haul and he found a skull in a bunch of seaweed. The roots of the seaweed had grown around the skull and kept it intact—the lower jaw was still attached to it, and you could open and shut the jaws with your hands. Morris was standing there, looking at the skull and opening and shutting the jaws, when I came on deck munching on a big juicy peach. Morris looked at me, and then he looked at that toothy jaw, and then he took sick. (1947)What is it about this work that keeps it going strong for nearly all of its slight more than 700 pages? Well, the back cover speaks of precision, respect, style, and graveyard humor, all of which is true, although I didn't register the latter as much due to how my instinctive lodestone for humor tends to revolve around the more subtly morbid varieties anyways. There's also Mitchell's wide range of haunts and interviewees, from Gilded Age barrooms to rent-controlled senior homes, half-anchorite ticket vendors to oceanographic expeditions, Harvard-educated bums and Mohawk steelworkers, clam beds and Black child geniuses, folks remembering the glory days of being on the payroll of those who owned the world and others drinking ketchup cause the diners don't charge for condiments. If any of those strike your fancy, you're in for a treat that certainly isn't of the 21st century style, but avoids much of the hateful nonsense that those periods were so prone to publicly exhibiting on the front page of their newspapers. Of course, and here I'm not going to be one of those who show their entire ass in complaining about 'shortened attention spans', but you do have to be some sort of information glutton to commit to the full spread of these, as when Mitchell draws out a narrative, he does so methodically without over-indulgent intricacy and directly without acrimonious sparseness. Long story short, if you're the type who questions why an article about a bearded lady needs to mention her belief that unboiled water is responsible for most of the sickness in NYC, or a why a piece about deaf-mutes gets into the nuances of employment agencies, you're not going to have a good time with this. I'm not even going to pretend that you should in anyway care about the sayings and doings of all these now-dead mostly white dudes as represented by another now-dead white dude. However, every so often, these stories spread a tendril into my brain and perked up a curiosity or a connection, or, even more rarely, reached under my ribcage and tugged on my heart just enough for me to notice, and that says something significant in the long run.

In Rome, in 1926, I sent a note to King Victor Emmanuel on a League letterhead. I told him I represented a multitude of right-thinking Americans, and we had a chat that lasted all morning. I got him so stirred up he talked the matter over with old Mussolini, and next year the two of them passed drastic laws against profanity. They posted warnings everywhere, even in streetcars, and arrested hundreds. I figure I'm personally responsible for ridding Italy of the profanity evil. (1941)Much as I refused to be sanctimoniously puerile in my analysis earlier, I won't go on about that tripe known as 'universal' either. I do have to say though that, sometimes, a writer peers behind the curtain of a country's mythos and finds that the people, especially the more disenfranchised, are just as interesting in the holistic way, if not moreso, as the tall tales they spin about themselves and each other. The problem, of course, is when an entire society is made to run on pageantry rather than civilization, and so long as one oligarch can buy and sell one dancing monkey, both public infrastructure and national quality of life can go fuck themselves. It was as true in Mitchell's time as it is in ours, the only thing having changed is how willing the public is to read about capitalistic devastation of local ecosystems or eradication of local affordable housing in their think pieces and not, in their discomfort, start connecting the dots between the haves and the have nots. So, we may have indeed lost something worth having between the time pieces like these were published and our modern day publications. But it has nothing to do with a lack of 'civil' arguments, or whatever is being peddled as the apolitical ultimate cause of culture wars. When it comes to a city like New York, New York, it gets the people and the culture and the arguments that it's willing to pay for, and if it continues to disenfranchise most for the sake of the few, not all the Mitchells in the world are going to be able to save it from itself.

So I was sitting on Uncle Miles's stone, thinking of the way things go in life, and suddenly the people in the longhouse began to sing and dance and drum on their drums. They were singing Mohawk chants that came down from the old, old red-Indian times. I could hear men's voices and women's voices and children's voices. The Mohawk language, when it's sung, it's beautiful to hear. Oh, it takes your breath away. A feeling ran through me that made me tremble; I had to take a deep breath to quiet my heart, it was beating so fast. I felt very sad; at the same time, I felt very peaceful. I thought I was all alone in the graveyard, and then who loomed up out of the dark and sat down beside me but an old high-steel man I had been talking with in a store that afternoon, one of the soreheads, an old man that fights every improvement that's suggested on the reservation, whatever it is, on the grounds it isn't Indian—this isn't Indian, that isn't Indian. So he said to me, 'You're not alone up here. Look over there.' I looked where he pointed, and I saw a white shirt in among the bushes. And he said, 'Look over there,' and I saw a cigarette gleaming in the dark. 'The bushes are full of Catholics and Protestants,' he said. 'Every night there's a longhouse festival, they creep up here and listen to the singing. It draws them like flies,' So I said, 'The longhouse music is beautiful to hear, isn't it?' And he remarked it ought to be, it was the old Indian music. So I said the longhouse religion appealed to me. 'One of these days,' I said, 'I might possibly join.' I asked him how he felt about it. He said he was a Catholic and it was out of the question. 'If I was to join the longhouse,' he said, 'I'd be excommunicated, and I couldn't be buried in holy ground, and I'd burn in Hell.' I said to him, 'Hell isn't Indian.' It was the wrong thing to say. He didn't reply to me. He sat there awhile—I guess he was thinking it over—and then he got up and walked away. (1949)