All Faculty Excerpts

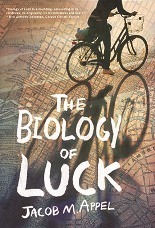

The Biology of Luck

Gotham teacher Jacob Appel—in addition to being a doctor, teacher, and prolific author of fiction and plays—has just seen the release of his new novel The Biology of Luck. It’s a highly original love story involving Starshine Hart, queen of the odd job, and Larry Bloom, a daydreaming/fiction-writing New York City tour guide. If you love good fiction, if you love New York, if you love love, you will love this book.

Gotham teacher Jacob Appel—in addition to being a doctor, teacher, and prolific author of fiction and plays—has just seen the release of his new novel The Biology of Luck. It’s a highly original love story involving Starshine Hart, queen of the odd job, and Larry Bloom, a daydreaming/fiction-writing New York City tour guide. If you love good fiction, if you love New York, if you love love, you will love this book.Here’s a brief passage with Larry:

###

Battery Park resonates with lust as the sun approaches its zenith. A primal impulse takes hold of the young couples strolling the gravel walkways, the newlyweds who have paused to admire DiModica’s bronze bull, the truant teens laid out on the cool grass, and maybe because they no longer feel obliged to respect the protocol of the early hour, the good breeding that proscribes sex in the morning, maybe because all flesh tantalizes in the early summer, in the right light, or most likely because, at this time of year, there is more flesh exposed, midriffs, cleavage, inner thighs, the park is suddenly transformed into a dynamo of painting and groping. This desire is not the tender affection of early evening, the wistful intimacy of the twilight’s last gleam. It is raw, concupiscent hunger. It devours decorum, banishes shame and flouts the loftiest ambitions of the penal code—and still thrives, unappeased. It is also an unwitting slap in the face to those deprived, those shackled by time and refinement, those deficient in the desire, in the performance, those too old, those too far away, those bereft, those who for one reason or another, clinical frigidity or clerical vow, but most often lack of opportunity, do not have a playmate to fondle among strangers. It is the reason that, on an ordinary June morning, Larry avoids the park.

Today is different. Striding across the shaded lawns at an invigorating pace, ignoring the Hope Garden and the Verrazano Monument and even the pubescent sweethearts dry-humping behind the Korean War Memorial, Larry stops at the base of the Walt Whitman statue to offer his gratitude. How many cold winter mornings has he stood on these very flagstones, the park moribund and barren, staring through the miasma of his known breath, invoking inspiration from the Bard of Brooklyn? How many evenings has he passed before the word processor in his study, eyes numb, forearms aching, spirit bankrupt, thinking of Whitman laying bricks in the torrid summer heat to bankroll his first edition of Leaves of Grass? Larry recognizes that he has embraced the wrong idol. Whitman had his devils, yes, but as different from Larry’s own as the scorch of fire from the burn of ice. Whitman had beauty, presence, grace; his agony lay elsewhere. Melville is Larry’s proper graven image. Melville: Near-sighted, homely, infirm Melville, the patron saint of the under-appreciated, scribbling away at his custom’s house desk through indigence, through ignominy, through the premature loss of his sons, denied both acclaim in life and eulogy in death. Larry knows that his altar should be Melville’s birthplace on State Street. And yet somehow he feels no kinship, no solidarity, with the Shakespeare of the Sea. Maybe Whitman is his star because Starshine is his subject, because she embodies all the spirit and splendor and sensual abandon that the Herman Melvilles and Larry Blooms of the world can only hope to experience vicariously. For Starshine is a Whitman poem, a blooming lilac, the body electric. Gazing up into the hero’s larger-than-life tribute, the maestro’s marble features beaming perpetually over a polished beard, Larry wonders if he has done justice to both master and model. He is certain he has. Other men expend their vitality in the act of living; he has consigned his ardor to the printed page.

###

Reprinted by permission of Elephant Rock Books

To read more about Jacob and his book, visit here.