All Faculty Excerpts

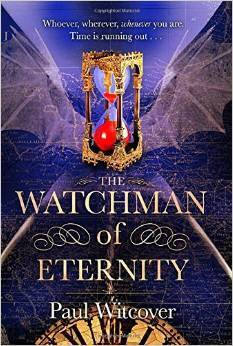

The Watchman of Eternity

Gotham teacher Paul Witcover recently saw the release of The Watchman of Eternity, the anticipated sequel to his previous book The Emperor of All Things. In this next installment, we return to the world of Daniel Quare and the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers as he sets out to find a deadly timepiece—a watch with a taste for blood. But a French spy/assassin is out to sabotage Quare’s mission.

Gotham teacher Paul Witcover recently saw the release of The Watchman of Eternity, the anticipated sequel to his previous book The Emperor of All Things. In this next installment, we return to the world of Daniel Quare and the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers as he sets out to find a deadly timepiece—a watch with a taste for blood. But a French spy/assassin is out to sabotage Quare’s mission.Steal a peek at this excerpt:

###

"Needful Things"

Aylesford opened his eyes in a soft, dry bed, in a room warmed by a peaty fire. He lay without moving for a while, half asleep, remembering like the drowsy ebbing of a dream how he’d cast himself into the storm-racked sea, trusting in the power of the relic, or rather the god within the relic, to bring him safely to shore. That act of faith had been rewarded, it appeared, yet he had no memory of how he had come to be here . . . or where, for that matter, he was. Yet this caused him no anxiety; he felt sure somehow, wrapped in warm contentment as he was, that the missing details would surface as sleep receded. All he need do was wait. And it was so pleasant to wait, to drift on idle currents of fancy that barely rose to the level of thought, as if he were again a wee bairn rocked to sleep in the sweet and loving arms of the mother he had never known.

Daylight streamed through cracks in the closed shutters of the single window and past chinks in the rough stones of one wall, pooling on the packed dirt of the floor. The wind gained entry likewise, circling the room like some small curious mammal with a cold nose drawn by the warmth of the fire yet too restless to settle down. The wind outside was bigger, wilder, noisier, though also curious in its way. It moaned and whispered and sighed. It whistled and boomed and buffeted. It rubbed its flanks against the sides of the house, sharpened its claws upon the stones. It was never silent or still.

The room’s ceiling was a peculiar mix of bound rushes, planks, fishing nets, and bits of stitched-together sailcloth. A spider had built a web in one corner, and evidently did not lack for flies. It hung there, patient and plump and prosperous as any innkeeper on the road to London; he felt comforted by its companionable silence, which seemed welcoming somehow. On the floor was a wooden chest—not, Aylesford saw at once, his own—and some mismatched pieces of Furniture—a chair, a cabinet, a dressing table with a mirror attached (only shards of which remained in the oval frame, filled now with fractured slivers of the ceiling)—that appeared, judging from their state of general disrepair, to have been salvaged from a succession of shipwrecks.

He hurt. It was that which finally roused him from his torpor. A distant throbbing ache, like the far-away crashing of surf, uncomfortable yet soothing in its rhythmic way, was all at once too near and insistent to ignore. Suddenly there was no part of him that didn’t register its painful protest. It hurt to breathe. It hurt to think. It hurt to be alive.

Wincing, and with a low, involuntary whimper such as might escape a suffering animal, Aylesford peeled back the bedclothes and regarded the naked body beneath. He felt like weeping. He did not recognize himself in this discoloured, swollen flesh, so deeply bruised, banded in livid streaks of purple, yellow, red, and black. He might have been looking at the painted body of an Iroquois warrior who had fallen in battle. Like all orphans thrown to the tender mercies of their fellow men, Aylesford had received his share of beatings down the years. Maybe more than his share. But never one like this.